Fair Water – Collaborative and fair catchment-based water management

In a changing climate, water extremes such as droughts and floods are becoming increasingly more common. Hence, cooperation between different parts of society to prevent damage and manage water under such conditions become critical to save life and property. Fair water is a project with Swedish focus, which aims to identify challenges and build consensus around risks and management practices of water in society.

Background

During the past century Sweden’s water resources been exposed to major changes. Some of the affecting factors include drainage of wetlands and lakes, water abstraction, dam construction and pollution. In addition to this, climate change contributes to more extreme rainfall, periods of drought and a shorter snow season resulting in reduced spring floods.

Water availability and fluxes are complex and dynamic as it is influenced by both natural variability and human alterations. Who gets access to the water? And how can we safeguard biodiversity while ensuring fair distribution of water, for both current and future generations? These are some key questions for Swedish water management.

Guided by the EU Water Framework Directive

In line with the EU Water Framework Directive, Swedish water management should be organised by river basins, rather than administrative borders. However, the management often relies on volunteer cooperation between many parts of society and administrative levels, which are often not in place. The collaborative processes are key to achieving holistic, sustainable and fair water management.

Floods and droughts are becoming increasingly common and affect society in different ways.

About the project

The aim of Fair Water is to strengthen collaboration between water actors for catchment-based and fair water management. The project gathers water actors and uses hydrological modelling and stress tests to simulate how water is affected by climate change, land use and water extraction. This provides an overall picture of the combined impact of many factors and the effect of various measures to avoid water shortages, flooding or poor water quality.

The results are discussed with stakeholders to co-develop sustainable solutions, which are functional for multiple users of the same water resource. Co-learning, exchanging knowledge, identifying synergies and resolving potential conflict is in focus.

Learning innovation labs

Together with water users and stakeholders, Fair Water develops new approaches for improved collaboration, communication and governing. This is done through a series of workshops – learning innovation labs. Here, participants can explore different approaches to water management and learn together about their effects.

We discuss the effect of decisions on competing or downstream activities and how resilient different sectors are to a changing climate. The project also highlights the effects of different governing approaches and showcases successful examples from other regions. The goal is that participants representing their own interests, together find new ways to handle situations that benefit both themselves and others.

The project is continuously evaluated, with the ambition to integrate results into regional and municipal water planning.

Research questions

- How can model simulations and stress tests help address current and future water challenges?

- How can conflicting interests and goals be identified and overcome?

- How can learning innovation labs be designed for Swedish water management?

The project is carried out in the Motala ström river basin in eastern Sweden, to develop methods that can be applied nation-wide.

Fair Water is run by SMHI in collaboration with Linköping University (LiU) and Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI).

Fair Water

Project period: 2023-2027

Financing: Formas, through the national research programme on oceans and water.

Partners: SMHI, Linköping univeristy, Stockholm Environment Institute, River basin association of Motala ström, and various stakeholders within Swedish water managemant.

Project manager: Berit Arheimer, SMHI

Project activities and results

Learning innovation labs

So far, the project has organized three learning innovation labs, with participants from the River basin association of Motala ström.

River basin associations exist across Sweden and are networks for collaboration and coordination between different societal actors, within a certain catchment area. Municipalities, county administrative boards, SMHI’s warning service, rescue services, hydropower companies and farmer’s associations are some common members.

Click on the headings to read more about the respective sessions of learning laboratories.

Lab 1 – Visions for fair water management

The River basin association of Motala ström was invited to the project’s first learning innovation lab in March 2024.

The aim was to create a shared vision around the project’s key questions, laying the foundation for future collaboration. The lab began with a short introduction to the project, followed by two exercises. Through the first one a common vision was defined:

"Establishing and maintaining a good process for collaboration to prevent and handle floods and droughts in the Motala ström river basin, for sustainable water management."

The second exercise was focused around three stress scenarios, visualized through maps, for drought and floods. Participants discussed what and who is affected and if the scenarios were too extreme, or not extreme enough.

Formulating common goals.

Lab 2 – Planning for extremes

In September 2024 a second lab was held, focusing on how to handle climate extremes. The aim was to draft a joint roadmap for achieving fair water management and to begin identifying multifunctional measures and solutions for extreme scenarios in the river basin.

Together we identified five categories of opportunities and solutions:

- Nature based solutions

- Technical or physical solutions

- Organisational and collaborative processes

- Insurance and economical incentives

- Law and regulations

- (Other)

Presentations during the project's second learning innovation lab.

Lab 3 – Exploring solutions

In March 2025, the third learning innovation lab was held. The aim this time was to explore and test solutions.

Using calculations by SMHI as a basis, participants discussed how different physical and nature-based measures in the landscape can help reduce drought and flooding. The goal was to jointly assess the impact and feasibility of different options.

SMHI provided calculations of effects on medium-high flow and medium-low flow for 12 different scenarios and measures. The calculations covered several areas in the river basin of Motala ström, which had been pre-selected together with the participants. Among the calculated measures were adapted regulation, irrigation ponds, wetlands, meandering of rivers and reduction of paved surfaces.

Jump to example calculations from Lab 3

The discussed questions included: What measures are possible? Where in the landscape could they be implemented? Who needs to be involved, and who has the mandate to act? What conflicts or synergies are present?

The joint analysis of the calculations came to a few conclusions:

- The effect of measures depend on local conditions.

- Regulating lakes seems most effective for managing large rivers.

- Irrigation of arable land may cause hydrologic drought in streams.

- Nature-based solutions, such as meandering/rewetting peatlands, have low impact on extreme flows.

- Irrigation, drainage, green cities and constructed wetlands can have some local impact on extremes.

Flood and drought scenarios

For the learning innovation labs SMHI develops scenarios of flooding and drought, on different scales. They represent extreme events with a long return period, that are possible but have not yet occurred.

The scenarios are based on historical weather events and water levels, which are combined in different ways to create the desired effects. With feedback from lab participants – the intended users of the scenarios – the scenarios are further developed to support better planning and identification of risks.

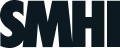

Example of flooding scenario

These scenarios were produced using flood mapping tools from SMHI. By setting different hydrological conditions, such as rainfall amounts and lake levels, scenarios of water flow and water levels can be generated.

The image on the left shows a scenario of rainfall amount and distribution equivalent to the extreme rain that hit the Swedish city of Gävle in 2021, had it fallen over the Motala ström river basin.

The scenarios in the second and third images were created by adding the rain in Gävle to already saturated soils and full surface water reservoirs.

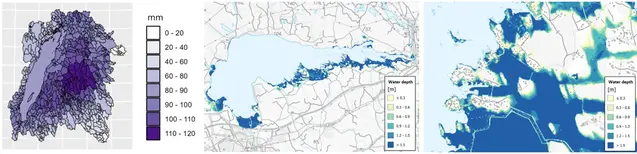

Example of drought scenario

This scenario was produced with SMHI’s hydrological model HYPE. The scenario is based on conditions during the dry winter of 2016 and the dry summer 2018, adjusted for a future climate that is both drier and warmer. The sequence was repeated for two following years.

Effect of landscape measures

In addition to flood and drought scenarios, SMHI has calculated the effects of different measures that can influence water flow in the landscape. These include a list of nature-based, technical, and physical measures, such as changes in regulation, irrigation, wetland area, paved surfaces and meandering of rivers.

Calculations have been made for several sub-basins in the Motala ström river basin, that already suffer effects of flooding and drought. The results have been used in the project’s learning innovation labs to discuss possible measures to prevent these hydrological extremes in the landscape.

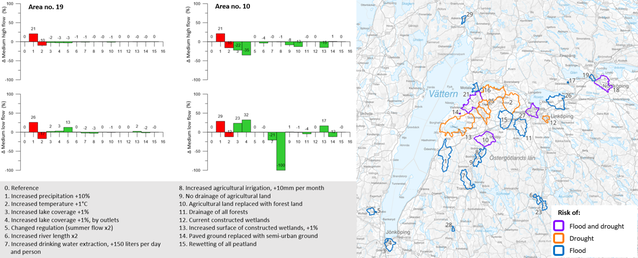

Example of impact calculations

The figure shows impact calculations for two sub-basins in the Motala ström river basin. Changes in medium-high flow and medium-low flow are shown in percent, as a result of 15 different scenarios.

The calculations were made with SMHI’s national hydrological model S-HYPE, using today’s weather conditions as a baseline. The first two bars show climate sensitivity, while the remaining 13 show the effects of different measures in the area. It can be concluded that the effectiveness of different measures varies greatly depending on the area.